How to Effectively Improve Old Habit Models

Clearly diagraming the anatomy of a habit can help us better understand what helps and hinders them.

The classic habit loop, as described by Charles Duhigg in his book The Power of Habits, is a cue, a routine, and a reward.

That model is great, but it quickly runs into problems when quitting vices. For Duhigg (and many in the self help community) you just sub out the cue or the routine in the loop. Quitting successfully is a matter of replacement.

Unfortunately that’s not always helpful if you’ve actually struggled with addiction.

ALTERNATIVE QUITTING PARADIGMS

The first time I quit smoking, I couldn’t replace the triggers - they were all around me, from the people I was with to basic, daily actions like waking up or eating. Also, changing the response was difficult because the habit and reward were jammed together. That hit of nicotine was the reward.

But when reflecting back on the quitting process, it felt as though I had just ignored the urge to smoke long enough until it ceased coming up.

Later I learned that this mental moment - a subtle point between cues and their responses - was key to a number of alternate quitting strategies.

Dr Judsen Brewer uses mindfulness to focus on it - it’s the backbone of his programs like smoking cessation and eating interventions. Dr. Lydia Zepeda, whose team ran the “Flash Diet” study, found that people who took pictures of their food before eating were able to make better changes than simply filling out food diaries at the end of the day. This acted as an intercessionary wedge between trigger and response in the moment of the action.

My own technique – tally clicking – emphasizes and separates out that moment by tying it to clicking a tally counter, simultaneously creating a metric of how many of those instances are experienced across time as the urge diminishes.

James Clear, in his book Atomic Habits, illustrates this distinction incredibly well in his updated version of the habit loop, adding “craving” to the classic model.

However, I think there are other inflection points not clearly delineated by the previous models. These can be divided into issues with:

Intentions

Leveling up habits

Transitioning when habit stacking

Love and connoisseurship

INTENTIONS THAT WORK

I can’t tell you how many people I’ve advised on habits who, caught in the throes of temporary motivation, just want to dive in immediately. They’ll have no plans in place, and most inevitably fail.

I think of a habit as a cheat code in the brain, like a shortcut, or a fold. The cleaner and more precise the fold, the more efficiently a habit will form.

A good intention is like a dotted line, pointing out exactly where to fold.

They should specifically point out triggers, the habit load, and preferably start out very tiny at the beginning. They should also include your why, possible stumbling blocks, and how to maneuver around them - what Dr. Gabrielle Oettingen describes as a mental contrasting exercise. Lastly, they should have a plan on how to expand.

Interestingly, intentions like this don’t even have to be done anywhere close to the habit. You can set them up days or weeks in advance. And as cues, urges, and habit starts migrate together, intentions become less conscious.

BALANCING HABIT LOADS

When habit loads are large, they tend to discharge badly. BJ Fogg will tell you that the smaller the habit load, the easier it is to start and and the more likely you are to keep doing it until automaticity builds.

But the change in habit load as you progress can also effect the entire process.

For example, if you jump from a solid 5 minute running habit to one hour, it’s going to erode the automatic nature of the Trigger/Urge/Response.

Leveling up that load is dicey. You’ll naturally grow, but at some point you’ll have to push it.

I’ve found that managing efficient habit loads doesn’t just involve willpower, but they can have a focus vector.

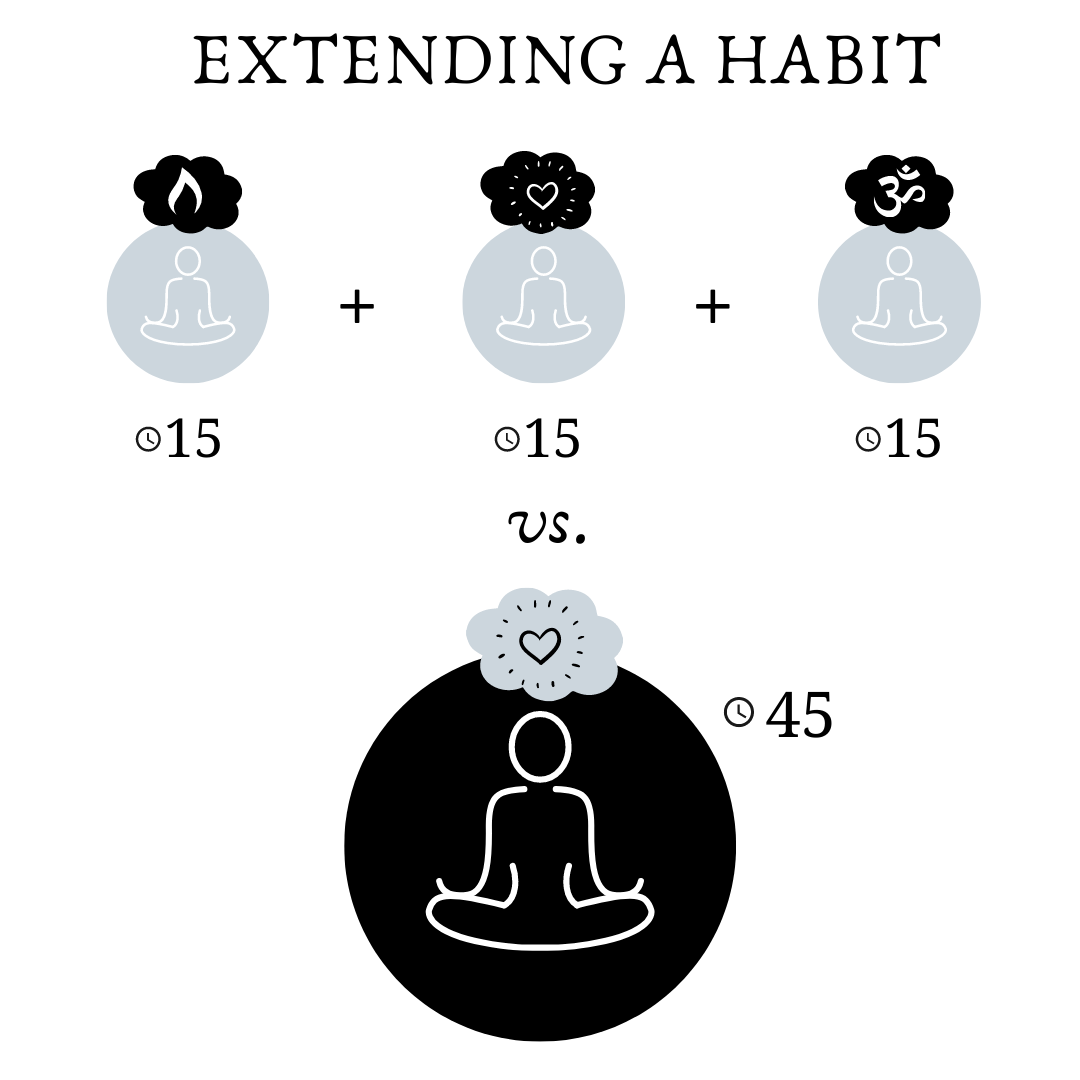

Doing 3 different types of meditation or cardio exercises back-to-back is going to feel subjectively easier than simply extending one type of practice. Similarly, 30 day challenges –which often include gamified elements – can also help level a habit load up without destroying it. Or you can just do it low and slow, like I did by adding a few teeth per week when leveling up my habit of flossing 2 teeth a day.

ENDING HABITS

We’re so caught up in starting habits that we don’t often think how best to end them. In the previous models, rewards are key. Personally, I don’t think they are necessary, but they certainly help accelerate habit formation.

What interests me more is how to lubricate habit stacking - executing habits back-to-back.

If the habits are similar to each other, there’s really not much of a problem. But what continuously occurs for me in my routine is a lag time if the habits are too different. I’ll just zone out.

In psychology, this is described as a task switching cost.

In habit stacking, bypassing this lag time is key. Priming a task is one method that has helped me overcome this. For example, I’ll watch short instructional Youtube videos of climbing if I’m transitioning between work and going to the climbing gym. It sparks my excitement and motivation enough to leap the task switching gap that can sometimes creep up between habits.

FALLING IN LOVE WITH THE PROCESS

Theres a central conundrum with previous models - they don’t have room to explain a holy grail of self-help: falling in love with actions.

Habits are automatic. As such, in my experience, a strong habit is mindless. And the inverse seems to be true. A recent study shows how directed attention seems to block the habit formation process. This makes sense since the previously mentioned vice busting strategies use mindfulness to break habits.

But it’s clear that people who report loving an action are incredibly attentive. Connoisseurs are almost mesmerized by minutae - like the way a cigar burns or how wine clings to the glass when swirled.

When I was a kid I used to absolutely love biking. It was exhilarating and intoxicating - I couldn’t wait to experience the colors, the smells, and as the air wooshed past as I peddled time seemed to dilate. And interestingly, like smoking, the act itself was the reward.

While the start of a habit needs to be automatic, something separate can occur in the habit load. You can have an automatically discharged start of a habit, but NOT have an automatic task load. In the meat of a habit (the “habit load”), there’s an opening for either mindlessness or mindfulness.

—

This newer model is really important because of this last point. How do you fall in love with a skill built on automation?

The automatic nature of a habit is important because it gives us that solid jump off point. But those who really soar are not the ones who mechanically master skills, but those who love even the imperfections and setbacks that are a natural part of learning. Falling in love is about appreciating all sides of the experience and growing from it in a vital, life-affirming manner that combines addiction, attention, exhilaration, flow states, and potentially unlocks massive reserves of energy.

By separating out the start of the habit from the habit load in this revamped model, we might be able to have our cake and eat it too.