A Better Way to Write: The Process Theory of Composition

The Writer sits at his computer, struggling to channel the Muse onto the depressingly empty page. It worked before, but today, everything typed ends up deleted. It was all so perfect the other day!

A common belief of writing is that it is an unchanging extension of the soul. Either we can write or we can’t.

In the opening lines of A Writer’s Coach, journalism professor and editor Jack Hart says:

“Novices sometimes imagine writing as a dark magic, something known only to some mystical inner circle. They pick up a professional’s finished work, marvel at its seamless perfection, and think, I could never do that.”

Later in the introduction he adds:

“The invidious mystique of writing taints the curriculum in almost every school. In literature classes, you read a great works and marvel at the genius of the writers who produced them. In composition, you struggle to knock a few clumsy sentences together. Nobody expects you to see any connection between the diva’s aria and your Neanderthal grunts.”

A better method is one that takes focus away from divinity. In the words of James Clear, an author and writer on habits, it is better to create long-term systems rather than short-term goals:

“Achieving a goal only changes your life for the moment…We think we need to change our results, but the results are not the problem. What we really need to change are the systems that cause those results. When you solve problems at the results level, you only solve them temporarily. In order to improve for good, you need to solve problems at the systems level. Fix the inputs and the outputs will fix themselves.”

I thought I was a good writer. My natural abilities got me far. As a columnist for National Geographic Traveller, my writing appeared in publications like Esquire, GQ, Vogue, and Conde Nast Traveller. But at several stages of writing I’d often be beset by writer’s block. I’d procrastinate, I’d obsess with one article, but more importantly, I was always uncertain.

In the newsrooms of the Oregonian, Jack Hart discovered that many veteran journalists had this problem. He, along with with a cabal of writers, coaches, and professors like Janet Emig, Peter Elbow, Chip Scanlan, and Donald Murray, emerged at the forefront of what became the Process Theory of Composition. Process composition championed the idea that writing, even at a high level, could be treated like any other craft.

The key is reducing tasks to component parts. Author Timothy Ferriss emphasizes this in his book The 4-Hour Chef, detailing a methodology to reverse engineer any skill.

He describes the first step, Deconstruction, as asking “what are the minimal, learnable units, the LEGO blocks, I should be starting with?” This prevents anxiety by eroding the scale and impossibility of complex behaviors. When applied to writing, it becomes clear that many issues originate from executing multiple processes at once.

As a nonfiction writer, my process involves layers of Creativity, Structure, Transitions, Ledes and Kickers, Research, and Polishing.

Over the course of this article, I’ll tackle each stage and offer general tips and tools. In the Appendix I’ll also provide a meta document with all of the layers I used to create this very article, which should provide a bird’s eye view of the process.

CREATIVITY

The blank page is always the first challenge for any creative. Perhaps the best methods to generate ideas surprisingly come from the world of advertising. On Madison Avenue, artists and writers were, perhaps for the first time, forced to adhere to corporate deadlines where millions were on the line. One powerful idea generator unlocked creativity by lowering standards, setting time limits, and increasing output. The key, however, is to treat it mechanically:

Creativity is a physical process, not a mental one. It's also something that can be easily taught through certain exercises. While some people are naturally more creative than others, those that aren't can make up for their lack of creativity through simple processes.

This activity, described to a Redditor by Rory Sutherland (an executive of Ogilvy Advertising) is called "scamping":

“The trick is to think as little as possible, and work as fast as possible. You'll probably start out with some dumb ideas. That's fine. The goal is to bounce from one dumb idea, to a less dumb idea, and so on. You'll soon find nuggets within these dumb ideas, and start building upon them. Personally, I wouldn't stop until I'd gone through an entire stack, which would take about two hours.

Once you're finished, it's simply a process of elimination. Go back through all your ideas and start sorting them into two piles: good and bad. Once you've done that, take the good pile and sort them again by good and better. Keep doing this until you've narrowed it down to five ideas.”

Game designer Nick Bentley describes a version of this as the 100:10:1 Method. Either method bypasses the muse – or at least summons her when and where you want. And though the idea of the tortured artist desperately searching for ideas appears ubiquitous today, it wasn’t always so.

In fact, in “Blocked", The New Yorker describes how it originated in a certain place and time.

“Writer’s block is a modern notion. Writers have probably suffered over their work ever since they first started signing it, but it was not until the early nineteenth century that creative inhibition became an actual issue in literature, something people took into account when they talked about the art. That was partly because, around this time, the conception of the art changed. Before, writers regarded what they did as a rational, purposeful activity, which they controlled. By contrast, the early Romantics came to see poetry as something externally, and magically, conferred.”

Another technique for circumventing blocks is to disassociate yourself from them. You can do this by framing the work as an explanation to a friend (that’s how this article got its start for me), or perhaps an argument with an enemy. Legendary journalist John McPhee’s advice is to write a letter to mom:

“You are writing, say, about a grizzly bear. No words are forthcoming…You are blocked, frustrated, in despair… What do you do? You write, ‘Dear Mother.’ And then you tell your mother about the block, the frustration, the ineptitude, the despair. You insist that you are not cut out to do this kind of work. You whine. You whimper. You outline your problem, and you mention that the bear has a fifty-five-inch waist and a neck more than thirty inches around but could run nose-to-nose with Secretariat. You say the bear prefers to lie down and rest… And you go on like that as long as you can. And then you go back and delete the ‘Dear Mother’ and all the whimpering and whining, and just keep the bear.”

STRUCTURE

If the ideas are the blood and guts of a story, then structure is its bones, the organizational principles that make it stand.

Most of us were taught outlining as children, but a better method that interfaces with scamping comes from Shani Raja, a former editor at the Wall Street Journal, Economist, and Bloomberg. In his Udemy course “Editing Mastery: How to Edit Writing to Perfection” he describes specific steps to construct a logical scaffolding for any article.

The steps are simple:

Atomize the ideas and list them out, one per line.

Tag each one with a general family marker.

List out all the families.

Rearrange the families in an order that works best.

Physically move the points to the families.

Physically rearrange the points within each family.

Jack Hart further talks about this in A Writer’s Coach where he dubs the process a “jot outline”:

You go through your notes and list the main topics you want to cover, jotting them down or typing them on the computer screen as you find them. If you’re using a computer, you then block-move those broad topics into logical order.

The act of writing down your few main topics, in order, gives you a step-by-step approach to the chaos of details you often face when information gathering ends. It relieves panic because it allows you to ease into the writing incrementally. It creates some distance between you and the story. And it’s a relaxing ritual.

If you’re facing a deadline, you may think you don’t have the time to outline. But you probably don’t have time not to. -A Writer’s Coach, p. 35

TRANSITIONS

When BBC documentarian David Attenborough transports you from Amazonian rainforests to the icy Himalayas the way he did it is what you forget. It seems effortless, like a wizard whisking you to another, far distant land.

Shani Raja describes them as “narrative turns.” They offer a smooth intro to each new section, forming a secondary infrastructure within the article.

And as a viewer you accept it, almost unconsciously.

Great writers, documentarians, and especially stand up comedians use them to elegantly shift from one, seemingly unrelated topic to another. In this blog post CEO and Kibin Co-Founder Travis Biziorek describes how transitions make or break standup routines.

Transitions are so important that Conan writer Laurie Kilmarten shared a compilation of them used as a go to reference for fellow professional writers on the show.

Categorization is key to breaking down processes, and in composition it allows writers to hone in and practice elements of the craft. By analyzing a number of articles, and how writers move from one topic to the next, we can classify transitions into categories. Luckily, there doesn’t seem to be that many of them. Over the years I’ve only been able to identity about 20, which I’ve listed in the Appendix.

LEDES AND KICKERS

Beginnings and endings are another stumbling block, even for highly advanced professionals. John McPhee even wrote an article in the New Yorker discussing his difficulty finding good endings.

But many of the process “wise guys” have solved this in the same manner that I solved transitions. Jack Hart had his “Lexicon of Leads” (Hart, p. 49), and Chip Scanlan describes his “Encyclopedia of Endings” in an article for the Poynter Institute.

The key is to simply analyze, categorize, and keep the lists as cheat sheets. I’ve included my expanded versions of both in the Appendix.

And when confronted by an actual article, follow Don Murray’s advice:

“Draft a dozen leads, or two dozen. Just the first line or so. Do it quickly – a matter of one minutes for each one – until you find the lead that focuses the story. Then develop that lead.” - Writing to Deadline, p. 135

RESEARCH

In the past, first drafts were the initial high wall to hurdle over and I often couldn’t make it. With the mechanics of the article sorted, the bar to jump is a lot closer to the ground. All the mechanics are at play, smoothly guiding you from introduction, families of points, transitions, all the way to endings.

However, research can easily become endless, especially when you’re writing nonfiction. That is why it’s best to do it at this phase. This stands in contrast with the usual method, with potentially endless research at the beginning. While I think research is often a necessary precursor if you don’t know what you’re saying or have absolutely no knowledge in the first place, the problem is that it can end up becoming a time drain. Perfectionism and completism, two traits all-too-common in writers, function to make this a dangerous stage where many never emerge.

If you’ve done some initial digging and know what you have to say, then follow the preceding stages first. Holes can clearly be marked with the tag “TKTK” - the traditional journalistic method for indicating that further information will be added later

Afterwards, fill in the gaps. With this, research is hemmed in and highly targeted. It’s more like a puzzle piece with clearly delineated borders than an infinitely deep, time-sucking maw.

POLISHING

While you might have the full article complete, it’s much like, as Stephen King describes in On Writing, a fossil that you’ve found, still buried in the earth.:

“Stories are relics…the writer’s job is to use the tools in his or her toolbox to get as much of each one out of the ground as intact as possible…To get even more of it, the shovel must give way to more delicate tools: air hose, palm-pick, perhaps even a toothbrush.” - On Writing, p. 163 - 164

I find polishing to be a matter of repetition. As with scamping, the key is writing and rewriting with minimal in-the-moment editing. Keeping a synonym finder open, continue changing small elements without really stopping, using intuition and gut reactions to know if a word or fragment is correct.

Done correctly it’s very similar to the adage of monkeys on typewriters producing Shakespeare.

The only difference is you’re using discernment to know when you’ve managed to hit on the well turned phrase.

Visually, this takes the form of a miniature bit of evolution, with the constant writing, synonym finder, and repetition acting as a genetic drift across successive generations. Meanwhile, your instinct in keeping fragments acts as natural selection protocol. The key is, like scamping, to make the process mechanical and continuous. This is a knack to be developed through practice, and I’ve mentioned methods to develop it in the Tools section.

But for Shani Raja, polishing is all about adding another layer, especially with implanting thematic elements and evocative verbs. He uses this stage to goes on a hunt for common mistakes, like redundant phrasing and passive voice. With Jack Hart, this layer can also mean adding similes, detail, and color.

GENERAL TIPS

While the nitty gritty is very important, here are some general suggestions for the overall process.

One great tip is what Hart calls his First Law of Writing Improvement:

“A problem visible at any one stage of the writing process usually results from something that happened at the immediately preceding stage.” - A Writer’s Coach p. 7

I have noticed this to be very true. In his MasterClass, James Patterson advises moving quickly from one draft to the next to prevent inertia from gunking up the system. While Stephen King doesn’t usually do as many drafts as Patterson, he does advocate finding the outlines of a story as fast as possible.

Don Murray harnesses this for problems with writing beginnings and endings. And while it may sound tedious to write so many, it tends to save time in the long run:

“Drafting leads or last lines can be a good technique for meeting a deadline. The time invested to draft just a half a dozen leads pays good returns if you find the right lead instead of stumbling through a piece following the false direction of a bad lead”. -Writing to Deadline, p. 11

All of these techniques put continuous focus on the mechanics of the entire process rather than individual stages.

PERSONALITIES

Another useful technique is to see each stage as recruiting different personalities.

According to Jack Hart:

“Somehow they’ve [productive writers] learned what appears to be the secret to successful drafting – operating with a split personality. They have one mind-set when they’re getting through a first draft. But they adopt a completely different approach when they go back to polish the copy into finished form.

The happiest, most productive writers approach their rough drafts as a literary version of Mr. Hyde. They cast civilized restraint aside, letting an uninhibited process of creation carry them quickly through the first version of the story. They don’t stop. They don’t revise. They don’t look back…

Only when they’ve finished with the draft do they slip back into a Dr. Jekyll persona. Then they sweat each detail, checking facts for accuracy, revising sentences for rhythm, and scrutinizing words for precise meanings.” - A Writer’s Coach p. 38

I tend to to use a few more personalities.

For scamping, imagine a part of yourself that’s a confident yet Whimsical Creative. I know several of these personality types, the ones that are free spirits, who often don’t have a lot of new or unique things to offer, yet boldly proclaim them as though they’re god’s gift to literature – spelling mistakes and all. Fundamentally, they believe that they are special and should be heard. Or alternatively, it’s the monkey on a typewriter, never stopping, gleefully pounding away to the music of the keyboard. This is perfect for scamping, rough drafts and some level of polishing, where cynicism is just not useful.

The Analytic is perfect for mechanical aspects of the process. He’s the guy who doesn’t like the confusion of soft skills, but loves puzzles and is utterly enthralled with simple tasks with discrete rules. Or, the Architect, focussing on the big picture, like Tony Stark amusedly designing the first Iron Man suit. Playing with concepts, he throws this away, keeps that, changes it up to look at different configurations on a whim with none of the urgency for a final product. The entire article is like a jigsaw puzzle, carved so every piece is unique and fits just so. This is perfect for the organizational phase, where word choice is inconsequential.

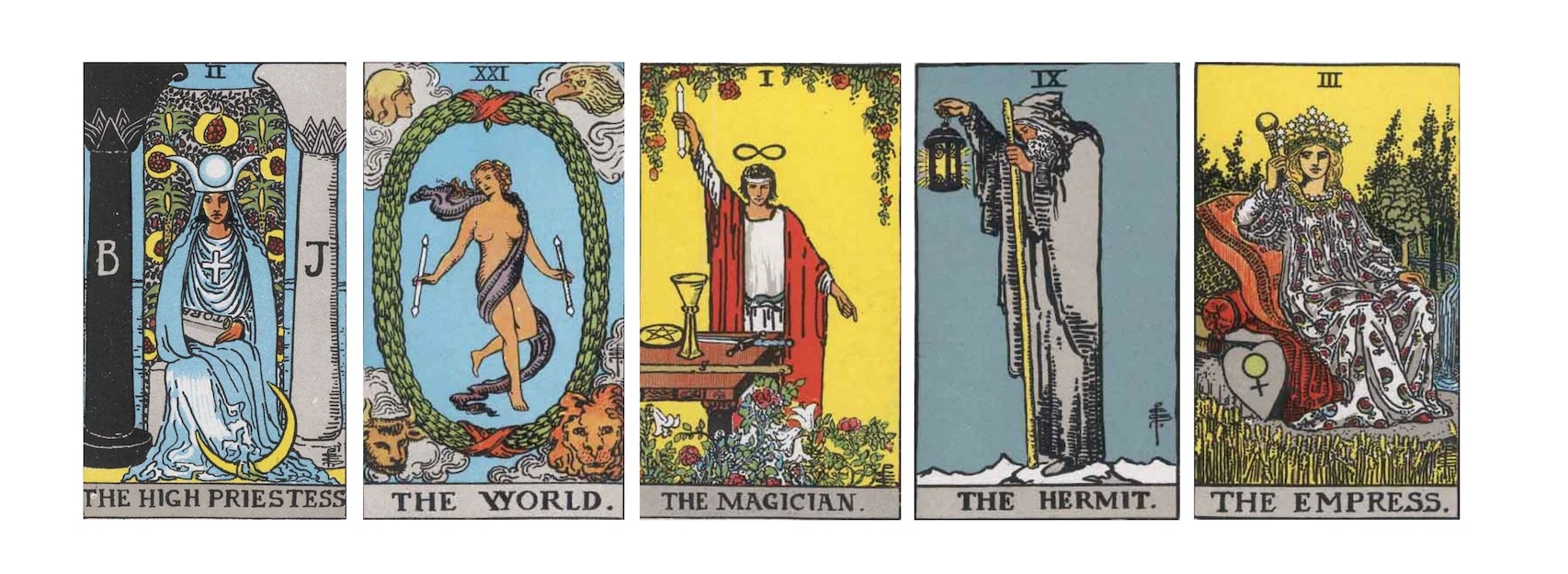

The Magician is trying to pull a beautiful fast one on the audience. His hand movements may be highly technical, his tricks may involve complicated bits of string or false thumbs that look oh so mundane in the light of day. But to the audience he’s effortlessly whisking them from one place to the next. These are transitions - there are only a few, they are very mechanical, but when done right you don’t even know they’re there.

The Archivist loves diving into facts and figures. She’s also a bloodhound and a detective, sleuthing for details. Bookish, she has to be held on a tight leash, but when reigned in she targets searches and comes back out again with summaries to be placed neatly into the holes carved out for her by The Analytic.

And lastly The Queen is the editor, she who must be appeased above all else. She’s arrogant, anal retentive, the ultimate fashionista with unquestionable taste, demanding the highest of standards. And if she doesn’t like what she sees, she banishes the section to another one of her earlier underlings. She’s the one in charge of the details and formatting.

The other steps are combinations of these personalities. The Monkey-Creative pounds on the keyboard to get through the first draft and for polishing a turn of phrase, though it works with the Editor/Queen to know what to keep. The Analytic works with the Magician for transitions, because really there are only a few and it’s a largely an act of matching the two together. The same occurs with beginnings and endings - there are only a few categorically, but the Magician makes it hit home with the panache of an entertainer, and the editor presides over it, making sure it all hangs together. The researcher is like a hermit searching for truth, but has to be hemmed in to prevent him from wandering off forever.

TOOLS

Luckily we don’t have to just rely on smoke and mirrors to recruit different skills.

Scamping can be practiced. National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) is a program that focuses on word output rather than content, with a supportive community and a gamifiied system in place to fuel mastering the art of pounding on the keyboard. While that was the system that really helped me master it, Write or Die is another method. It offers a mode where the program starts deleting words if typing stops for a few seconds, forcing users to write with, as the Guardian put it, “a virtual gun to the head.”

Writing coach Don Fry suggested writing with the screen blank if you’re encountering resistance completing a first draft. Complete a jot outline, print it out, position it on your computer monitor, and begin typing. This forces you to ignore typos or grammatical errors. Since you don’t know where you are you have to go all the way to the end (from A Writer’s Coach, p. 40).

Online synonym finders are incredibly useful for discovering that word that’s the perfect choice but just outside your mind right now. Some offer visual similarity and meaning maps, with options to select for length or starting letters.

Brainy Quote is a great tool for beginnings and endings. While the quote-beginning or quote-ending is somewhat passé, it is definitely a great welcome addition, and can spur on thought on other avenues to begin and end pieces.

Having a list of Transitions, Ledes, and Endings on hand is key for those sections. I’ve included these lists in the Appendix.

Scrivener is a fantastic program for layering drafts, and easily moving back and forth between them. You can view split screens of different drafts, which is handy when, say, writing a first draft while looking at a skeletal outline. It also has a cork board feature where you can move categories around visually.

When looking at the big picture you have to learn to “kill your darlings” - get rid of smaller aspects that you might really like in order to further the work as a whole. Shani Raja says that he used to either print the article out, or change the font and size to act as though the piece you toiled over is someone else’s, subject to brutal objectivity.

One of the best pieces of writing advice comes from fantasy author Brandon Sanderson, whose excellent writing classes are recorded on Youtube: Always be working on something. It’s echoed by many other prolific writers. It helps in terms of pitching and in disassociating to maintain objectivity in edits. Sometimes you get too close to your work, and taking time off, ideally by working on something else, is key. For that I use Trello.

Often touted as software for collaboration, I find it useful to visually keep track of multiple projects. With it I can enter into any writing stage and know exactly where I am and what I need to do. If I get tired of one stage of the writing process, I can go and work on another stage with a different article.

CONCLUSION

This manner of writing is dramatically different than the traditional method.

For one, there’s a reliance on external tools. When you’re constantly referencing lists of ledes, or robotically reordering thoughts to produce structure, you emphasize how mindless the entire process can be. And that has clear benefits. Overthinking is perhaps the leading cause of writer’s block. And idea generation appears to be fueled by NOT being so attentive. The ability to push forward on writing despite being tired or distracted results in constant forward momentum.

The line between mindless and mindful also offers a great diagnostic tool. When discussing Olympic lifting in his book Becoming a Supple Leopard, physical therapist Kelly Starrett explains that stressors reveal faults in the process. Add more weight or faster repetitions and a coach can clearly see the weaknesses in the mechanics of the lift. When adding stressors – writing while tired, with distractions like a TV on, or writing for time – the process writer can spot weaknesses in the procedure. The cure is often more training or breaking down the process into greater detail.

The process method offloads weight from needing to think really hard about any one thing. This results in greater output and the ability to write virtually anywhere. More output allows for more opportunities to practice, rather than being cramped and stymied by needing a commission or a perfect place to concentrate. It also prevents the biggest problem in writing - psychology. Writer’s are often crazy alcoholics, drug addicts, or depressed - even the successful ones end up committing suicide. There’s a reason for this. There are no metrics for good writing. Almost any other type of learning has something our minds can latch onto to improve. And if we can’t clearly improve – or assume writing is a function of who we are – happy writers become the exception.

Over the last few months I’ve experimented heavily with this method, and it feels weird.

As you can see by my Trello board, I’ve worked on 13 projects at the same time, at various stages of the process. When asked asked what subject I wrote about that day, I usually draw a complete blank. But I can describe what steps of writing I was working on. Before, I was obsessed with one article because it was make or break. Now, it’s not the subject that’s important. I’ve already noticed a dramatic improvement in each step - the smoothness and ability to create 3 transitions between each two sections, or come up with 10 ledes. Once you start actually practicing – something I realize I never did – you adapt quickly.

I learned a lot about writing from visiting the Picasso Museum in Barcelona a few years ago. Rather than only showcasing his famous pieces, the museum displayed an encyclopedic catalog of the artist’s life, where each room was a phase of his creative development. I was lucky enough to go with an artist friend, who beckoned to a realistic sketch of a hand. “This,” he said, “is where you knew he was going to be great.” Each room demonstrated Picasso mastering a vocabulary, a specific, almost surprisingly commonplace, style. These were the solid building blocks used to fully express himself in the unique manner we all know today.

In writing we all-too-often minimize the discrete skills. And yet, only when process is king and the humble steps mastered can we make the leap towards art.

APPENDIX

Here’s a list of tools and resources mentioned in the article (and a few additional ones thrown in for good measure):

PROGRESSIVE LAYERS FOR THIS ARTICLE:

WORD FILES:

Jot outline with labels

Categories listed

Categories reordered

Points moved

Rearranging points within categories

Adding transitions

Ledes

Kickers

First draft

Research

Second draft

CHEAT SHEETS:

BOOKS and ARTICLES:

Jack Hart, A Writer’s Coach: A Complete Guide to Writing Strategies That Work

Timothy Ferris, The 4-Hour Chef: The Simple Path to Cooking Like a Pro, Learning Anything, and Living the Good Life

Nick Bentley, The 100:10:1 method – the heart of my game design process

The New Yorker, A Critic at Large, Blocked: Why Do Writer’s Stop Writing?

John McPhee, The New Yorker, Draft No. 4 (Also a book by the same name)

John McPhee, The New Yorker, Structure: Beyond the Picnic Table Crisis

Don Murray, Writing to Deadline: The Journalist at Work

Chip Scanlan, The Poynter Institute, Putting Endings First

Stephen King, On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft

Steven Pressfield, Do the Work

Robert Gottlieb, Paris, Home of Le Burger

Vir Bala Aggarwal, Essentials of Practical Journalism

COURSES:

Shani Raja, Udemy, Editing Mastery: How To Edit Writing To Perfection

Shani Raja, Udemy, Ninja Writing: The Four Levels Of Writing Mastery

James Patterson, Masterclass, James Patterson Teaches Writing

Brandon Sanderson, Youtube/Brigham Young University, Write About Dragons

Holly Lisle, Holly Lisle’s Writing Classes