How to Get to Sleep Faster: A Sleep Hygiene Checklist

Good sleep starts long before you climb into bed at night. Start getting better sleep with this sleep hygiene checklist.

Read MoreGood sleep starts long before you climb into bed at night. Start getting better sleep with this sleep hygiene checklist.

Read More

Last week marks the first time I’ve ever reached the end of any planner.

(I also ran out of ink - also a first. I’ve usually lost my pen well before that ever happens!)

I evolved and learned a lot in the last 20 months since formalizing a planning habit.

I started with Bullet Journaling.

I found it incredibly adaptable. It let me make up sheets as I went along - from jotting thoughts to taking notes at meetings. The indexing system helped me keep track of it all (even though I started getting lax at going back and actually indexing pages).

It helped me accomplish tasks at different rates. Early on in my planning journey, I used the metaphor of compound interest towards long-term projects. If I was consistent about doing them, it didn’t matter if I only did a little bit a week – the work surprisingly added up fast. My tendency is to work linearly, attending to tasks that need doing now. But working in 10 to 40 minute sets per week helped me finish big tasks like a grant proposal, a fellowship application, and a book proposal. I was even able to finish a book for a club discussion without panicking and cramming the reading all at the last minute (which has definitely been my M.O. in the past).

It helped me develop long-term strategy. I did this by focusing on the low end of output and time (planned mediocrity). Overestimating the time needed for a task better equipped me to see where I’d be the next week instead of hoping to be there. The added psychological benefit was that I tended to exceed expectations.

A planning habit also worked wonders with off-time. “Weekend menus,” which I’ve used in the past, came back in a more consistent manner, and I felt more energized, attended more organizations, and explored more of my city as a result.

I created flowcharts for standardized tasks, and also learned how to plan a trip. Although I’ve traveled a lot, I’ve always been reliant on happenstance or Lydia’s amazing planning skills. I planned road trips, national travel, and even city exploration of different neighborhoods. It’s developed into a replicable system that gave me a sense of competency, which really can’t be emphasized enough.

Lastly, I created a robust planning metric. In the past I’ve found that a solid assessment of a behavior allows me to try different techniques to see what works to improve scores. This worked wonders for my sleep, and this simple planning index showed me where I needed improvement on a week-to-week basis. I intend to publish it as a post of its own, but here I’ll reveal that it assesses the number and types of tasks, emotional calmness, adaptation ability, and time estimation accuracy. It’s a work in progress, but I’m still quite proud of it as a practical diagnostic tool.

But not everything worked so well

Lydia suggested separating days to focus on specific tasks - like “pitching Mondays” or “social media Wednesdays”. This didn’t quite stick. Nor did attempting a project-oriented graph, like what Brandon Sanderson does for his work.

Which is unfortunate - in one article Holly Lisle mentions how she can project with accuracy how long her books will take to write. That’s something I envy, but is pretty difficult without knowing for sure how long specific tasks (like creative ones, or editing) take. It’s all the more frustrating because in many instances jumbling tasks up is the most efficient way to do them, even if it’s hard to time.

For example, after I finish a first draft, it’s better to take a break and do something else before editing. You gain some distance, and are able to view your writing with fresh eyes. But it’s more difficult to time a project when you’re threading it with other work.

So I bought Timeular - a dice-like gadget that times various projects depending on how you hold it. Timular will show you how long Task A takes overall even if you’re interrupting it constantly with Tasks B and C.

However, I had a problem using it because I wanted to somehow divide tasks according to their behavioral efficacy. If Task A is made up of tiny tasks of editing and creativity, then those need to be treated separately and are best planned out to match my energy levels. Creative tasks are best done when tired, analytic tasks like editing are better done when alert.

This issue of syncing up broken up projects and smaller behavioral tasks is a huge mess that I’m still working on.

Assigning tasks was really problematic because there ended up being three different things to take care of: Whether I was distracted or not, whether it was early or late in the day, and how to fit it all into days of the week.

Furthermore some tasks were contingent on other tasks, others were emotionally draining, others required help, etc.

My attempt to create a BUJO-style key that included behavioral elements

I was also bad at looking at the big picture. Looking over this notebook, I can see how I still lack a true method of long term strategy. Circling back to hone in average task times almost never happened (other than a weekly post mortem to see how I did on the planning metric). And I also didn’t have a set time to go back over to-do items, causing a lot of tasks and reminders to get lost in the cracks.

Long term strategy and emotional tricks are two standouts I need to work on. The idea of somehow becoming utterly calm and unflappable, while at the same time getting a lot done on multiple types and rates of projects, is incredibly appealing.

I’m also looking into nonlinear planning, an odd subsection in artificial intelligence. It’s used to create programs that partially solve problems that are contingent on solutions from other partial solved problems. The more I delve into it, the more I realize just how often this becomes a problem in people’s day-to-day planning, but virtually no one seems to talk about it with any rigor.

—

My inability to plan has adversely effected my growth in all sorts of arenas. But on the whole, creating and taking my planning metric forced me to figure out basic things I had never thought about - like my average work load. Systematically progressing and strategizing like this is a weird feeling, like finishing an entire planner. And it can only get better.

Over the last few weeks my system has glitched.

When my meditation course finished, I floundered.

I borrowed a rower, but I had to return it as soon as I developed a strong, basic habit. When I pivoted to walking, it got really hot and my habit was inconsistent. And my covid reset attempt fizzled out within a few weeks.

One thing I’ve learned in this project is that there’s always a reason for why things fail that’s more complex than “I just couldn’t do it”. And there were plenty of reasons for failure here.

Enacting all these changes at once was dicey to begin with. A global pandemic, race riots, and a very intense meditation course didn’t help either.

But more importantly, there were deeper, systemic flaws.

In the sci-fi show The Expanse, Joe Miller is a cynical, world hardened gumshoe who describes the dangers of walking into rooms.

“I keep warning you. Doors and corners, kid. That’s where they get you.”

I feel that’s a good metaphor for my recent failures.

When my rower had to be returned (like I knew that it would) I didn’t have a plan. When my meditation class ended, I didn’t know how to step back into a normal practice. And that’s consistently the biggest problem at the end of any challenge or growth cycle.

Sometimes it works on its own. When I went back to my normal writing after NaNoWriMo, I just naturally wrote more. But such natural growth all-too-often just fizzles out.

One way to navigate these danger zones is a more robust form of mental contrasting.

In mental contrasting you project ahead to any barriers you think you’ll have in your bourgeoning habit and figure out strategies to overcome them in advance. This usually includes alternative activities. If, say, it’s raining and you know you won’t run in bad weather, you’ve got to plan around that.

But another obvious element to include is how exactly you’re going to grow the habit.

I didn’t formally do this for rowing at all – even though I knew the rower wasn’t going to be here for long.

Addressing the big picture involves knowing what the next transition will be in order to level up a behavior. If I had planned to switch to another exercise habit and formalized it, I might’ve known that walking in the Texas heat would get to me.

If cross training and pushing a habit are the “corners” in this metaphor, then life transitions are the doors. Visits, travel, the end of a job or the start of a new one - life intrudes, and when it does it disrupts the system. Suddenly cues that were automatic aren’t so strong any more.

One way to transition is to plan a break. They’re critical for rejuvenation, yet I only really take time off when I’m forced into it kicking and screaming.

Another way is to abruptly end a habit and start a new one. In a previous post (“Killing Habits is Just as Important as Forming Them”), I talk about how it’s important to set a transition point, and suggest that 3 months might be a good time to do that even if there’s no other external change. A formal hand off to the next set of cues to crosstrain a skill-based habit is imperative.

However, I think that there might be a better method. In THIS post, I theorize an “unzippering” method to create two habits for the willpower price of one. I think I might be able to use this theory to splice in a new habit into the ending of the old one. This would allow for a smooth transition between multiple habits within a lifestyle such as exercise.

If I had tapered off my rowing habit while on-ramping walking, maybe I’d still have a continuous workout lifestyle right now.

—

All of this requires quite a bit of planning to orchestrate with any amount of continuity. That’s a skill I’m still working on.

But Detective Miller was right – Plans perish in portals and passages.

I don’t intend mine to die quite so easily.

When planning a skill-based habit, always include the plan for the next progression

When mental contrasting, be on the look out for any personal transitions, whether it’s a trip, a visitor, or the ending of a class or challenge. Prep for what you’ll do right after that point.

Plan time off.

Try to smoothly transition from one habit to the next in a lifestyle.

In the original version of the legendary cooking show, Rokusaburo Michiba was Iron Chef Japan. While his opponent rushed and sweated, Chef Michiba moved with unhurried deliberation, calmly writing his menu in calligraphy at the start of each match. It appeared unthinkable that he’d make the requisite 4 dishes.

Yet no matter the pressure, he’d serenely chop and stir, always at the right place and time. When the match concluded, he had extra dishes to spare, while his opponent slumped in exhaustion (and eventually, in defeat).

That’s how I feel – rushed, overwhelmed, and ultimately defeated.

While I now have a strong daily planning habit (using the bullet journaling method), I still can’t set long term goals and execute daily tasks to reach them with any efficiency.

A big problem is that I bullet journal what I INTEND to do in a day, which is often a too optimistic reflection of what I hope to do. Anything I don’t finish gets rolled over to the next work session.

That’s normal, linear planning.

Unfortunately, with freelancing I can’t plan linearly. I need to meet rotating deadlines at different rates, and cover for punctuated times of frenetic work or bottlenecks in pitching pipelines.

I need to break goals up into what I OUGHT to do in order to reach deadlines.

One method is to work backwards. Youtuber Clark Kegley advocates writing down large goals, often divided up by quarter. He then lists out specific methods to get to those goals.

Claire at minimal.plan suggests using a mind map to brainstorm every small thing you’ll need to accomplish those large goals. This has the added benefit of employing the Elements of Tiny Behaviors and Momentum, especially if you’re gamifying it all with checklists.

I’d add that a good scamp (free writing as many ideas for breaking down a task without regard to editing or logic) works wonders here - in fact, that’s what works well when I plan travel.

After doing a free writing session for an article, I then use a filtering system based on logical progression. For trips, it’s usually based on when things are open and my location.

Here, I can use a system based on task priorities, then assign time estimates.

Unfortunately, I’m woefully unprepared to give good estimates. Lydia suggests just guessing and then honing in on correct times once you do a task a few times. Another method is using a device like Timular or Timeflip, where you turn a dice-like contraption to track different activities. Users say the tactile nature increases adherence, which is important. I briefly attempted virtual timekeepers like Toggl and just kept forgetting to set them.

An important element I’m missing in estimating tasks is emotional weight. Tasks like pitching are incredibly draining - so including a mental technique, like the smiley face self-esteem games from McGill University that I wrote about before (which have been shown to boost optimism) is a must. Folded into task scheduling, they would prevent the day from devolving into a mental health disaster.

Mental space for decision making is also key. Decisions take energy and should not be relegated to a dusty side bin of planning when they take as much or more effort than any given task.

I’m also missing a planned time to review goals and hone in on better time estimates.

Planning should be a living, adapting process, evolving for the next quarter instead of the one and done action it is now.

“Brain dumps” of goals and tasks aren’t a problem - I do that now as a part of of my current planning and it’s been incredibly helpful.

But filters are needed to assign tasks across a day. Lydia suggests morning, afternoon, and evening assignments. She also suggests primary and secondary tasks for off times and overflow. Another method is having an A and B task based on difficulty. I’ve found that having an easier standby task to switch to greatly increases focus and efficiency.

She also breaks up tasks by days of the week. Monday, for example, could be a designated pitching day. That way you’re able to start breaking up tasks into different rates. Like a river, in freelancing some output is immediate (like social media or blogging), others are medium (magazines) and some are glacial (like proposals).

Behavioral filters are also needed. If you’re tired, creative tasks are optimal. Tasks that take more willpower, like decisions, emotionally draining tasks, and ones that require more processing power (like editing) should be filtered from ones that are lighter or automatic.

Frequent projects are best standardized as flowcharts. Emotions, willpower drains, lag times and techniques to counter these should be included as a part of the process.

While general lags come from task switching, there are larger blind spots that occur in mesocycles.

Whenever a 3 month project finishes or when I come back from travel, there’s usually some sort of glitch where all my systems fail.

Planning time off is something I’m really bad at, and these are the spots where it should be incorporated.

Moving forward, I’d like to hone in on my ultimate planning process. In the tradition of this project, that involves testing out new systems like:

Breaking monthly or quarterly goals into minute tasks

Estimating task completion

Using tactile time trackers like Timeular or Timeflip

Creating a filtering system

Including decision making and off time in planning

Creating a flowchart for common tasks encompassing bottlenecks, lag times, and common emotional issues

Collating the data to improve the next quarter

But how do you really know it’s working?

If there’s a metric to planning, it would incorporate the capacity to execute all the tasks that you’ve laid out in a given time. It’s also achieving a lot while not getting burned out. At the same time, a good planner is able to smoothly adapt to change, not only in the moment, but as an overall process.

In short, it’s becoming an Iron Chef.

Yesterday was one of THOSE days. I woke up with absolutely nothing left in the tank.

I was at the edge of just taking the day off when I thought - why not make it an experiment?

Would using all my protocols help out, even on my worst day?

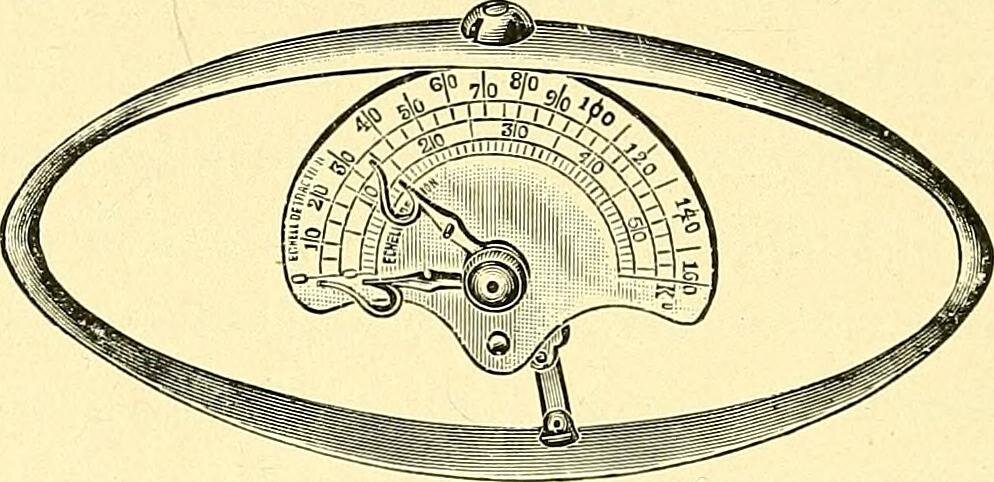

So I wrote down a plan of action and decided to break out my vintage, 1800s hand grip dynamometer. In a number of studies, hand grip was shown to correlate with self control. The intro of this study has a great break down of the history of using a dynamometer to do this (and its limits).

Here’s a chart of my data, with the X axis indicating grip strength. I took measurements before and after a round of work and before and after I engaged in willpower repletion protocols.

Here are my notes:

Starting Grip Strength: 40

Round 1

Read NaNoWriMo Pep Talk by Maurene Goo [EXEMPLAR PRIMING]

Read list of accomplishments [EXEMPLAR PRIMING]

Read affirmation questions [EXEMPLAR PRIMING]

Grip Strength: 70

Drop set - 3 Pomodoros of 10 minutes, started with automatic actions [TINY BEHAVIOR, SEQUENCING]

Mini meditations of Kawaii, Faster EFT, and Mindfulness for 1 minute breaks [KAWAII, MINDFULNESS]

Grip Strength: 65

BREAK

Food outside [GLUCOSE]

7 min row, slow pace

7 min stretch

Grip Strength: 65

Round 2

NanoWrimo Pep Talk by Jasmine Guilory [EXEMPLAR PRIMING]

Smile Games [EXEMPLAR PRIMING]

Grip Strength: 71

Drop set - 3 Pomodoros of 10 minutes

Mini meditations of Kawaii, Faster EFT, and Mindfulness for 1 minute breaks

Grip Strength: 65

BREAK

Stepped outside for about 20 minutes

Round 3

Smiley face game [EXEMPLAR PRIMING]

Affirmation questions [EXEMPLAR PRIMING]

Grip strength: 80

4 Pomodoros of 10 minutes

No breaks

Grip Strength: 50

Creating an initial system using Curiosity (“could I replete willpower when starting with nothing?) and Metrics (the grip strength measurements) to test out Elements was the first strategy that worked well. It created a distancing effect that kept me from experiencing the exhaustion as much. It’s a technique similar to mindfulness, which has been shown to help with cravings and engage self control (here’s a video of Dr. Judson Brewer describing how mindfulness has been proven in clinical trials to break the addiction cycle).

I noticed that my exemplar priming exercises all really helped out quite a bit to boost self control, and this was reflected on the grip strength tests. It was also further evidence that exemplar priming works better for me when I’m depleted.

NaNoWriMo has an easily accessible list of pep talks that I could just randomly click on. Question based affirmations can work even better than statements according to one study, and they especially tend to work well to boost me in particular. And surprisingly, the McGill University smiley face game which I previously wrote about also actually works really well - though in this case I used a similar mobile app called Upbeat Mind.

I found myself gaining energy across the day, an effect I attribute to Momentum – gaining a series of wins.

I used a shotgun approach of meditation techniques for small breaks - mindfulness, cute pics of animals (listed as Kawaii in the Elements), and faster EFT, which seems to work really well for me (I still don’t quite know why it works).

You can read more about “microdosing on meditation” in a previous post.

I tried to incorporate movement for larger breaks. My rowing and stretching habits are both triggered after my first round of work, so this was naturally built in. My rowing habit is also still in its early stages, so it is not hard enough to exhaust me yet. I also tried to incorporate sunlight by standing on my balcony. It’s not quite Forest Bathing or going on a walk, but it felt like a similar, smaller version.

I got cocky towards the end. My grip strength increased significant later in the day, and I just kept blowing past all my planned breaks and continued on to do a full Pomodoro load instead of a smaller set. This caused me to become utterly depleted. My grip strength dropped by 30 points and I definitely felt it.

There are definitely things I neglected to do. I didn’t drink my concoction of apple cider vinegar and matcha after lunch. I could’ve taken a walk, or even looked at pics of green landscapes. I could’ve done a gratitude exercise, or shifted to more creative, automated tasks when I saw my willpower was lower.

But the key problem was not having everything clearly planned out. When you get depleted, making decisions and trying to come up with new measures on the fly is almost impossible – you have to have it all pre-written to prevent decision fatigue.

In term of work output, this doesn’t seem like much. But when you factor in that this is Cal Newport-style “Deep Work” - no distractions, no emails, no social media, absolute concentration, then this is, for me, quite substantial. I didn’t include the work and exercises for my relatively intense meditation course or several errands. Nonetheless, if I had time, I would have definitely kept going.

Does hand grip strength accurately measure willpower? The science seems inconclusive, and there’s a lot of debate as to willpower in general. There are also many variations as to how studies conduct testing in order to negate natural strength. In my own testing I just took readings after keeping it squeezed for a few seconds without much effort and without psyching myself up. I also did not attempt to “spike” the measurement - I just wanted even, steady force.

However, this accurately correlated to my subjective experience of how depleted I was. And it’s something I really want to use for future measurements, though perhaps with the more updated versions of the hand dynamometer. I believe that it could be used to formulate a mathematical equation for productivity. I also think it could help test what repletion exercises have the most impact. It would be nice, for example, to know that exemplar priming tasks have more bang for the buck than looking at green landscapes, even if it only applies to me.

All of this seems further proof that engaging some sort of willpower muscle isn’t fully necessary for productivity. This was a clear case where the entire system “carried” me throughout the day. That was profound, because I realized that starting willpower - that feeling of mental focus at the beginning of the day - isn’t as important as it once was to me.

This is further evidence of a possible “Polymathic Engine” - a system that delivers massive amounts of self change using very little willpower.

Before reading Cal Newport’s amazing book, Deep Work, I just tried to work as much as possible. As a freelancer, that had many downsides: I didn’t get much done, and work would bleed into my off time. I felt like I was working 24/7 without any real understanding of efficiency.

Deep Work made me confront how I actually used my time. In it, Newport suggests that most of our “working” isn’t really focused. Instead we’re multitasking, and according to the neuroscience, multitasking well is largely a myth. We tend to badly switch back and forth between important tasks that need concentration and small distractions. And in today’s smartphone-filled world, the constant social media beeps and buzzes exacerbate the problem.

His solution is to learn how to formally focus. He advises turning off cell phones and blocking distracting websites. He even advocates short spurts and writing down what you’ll do TO THE MINUTE. The result is serious, efficient concentration.

I applied Newport’s theories by creating a deep work ritual. I used Pomodoros, blocked Facebook and Reddit, played non-distracting music, and wrote my times to the minute. And he is right - I’m laser focused, and I get more done.

The problem is that after about an hour and a half I’m exhausted.

[SKIP TO THE END FOR THE SHORT VERSION]

Newport suggests (deep) working up to 4 hours a day. There are days I’ll dig deep and extend it to 3 hours - but those are standouts. A good system works on its worst days. Was there a way to automatically lengthen out Deep Work?

To start, I noticed there were times where it just naturally happened.

The standard Pomodoro protocol on the app I use (Tomighty) is four sets of 25 minutes, separated by 5 minute mini breaks, followed by a larger 20 minute break. However, when I wrote 50,000 words in 5 days for National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) I quickly found that 13 minutes was more optimal - it was the average time my concentration for free writing broke (as opposed to this awesome research on optimal sets using an analysis of 5.5 million users). Later, when I lowered my normal work load to 10 minute sets, I felt (and still feel) my focus is stronger. But I’m also able to automatically do more repetitions.

As with my sleep study, which forced me to create a better sleep index, there were just too many variables. So I came up with a general metric for good work. It combined 4 elements:

Time to start

Focus in session

The number of Deep Work sets

Overall energy/torpor

The biggest issue was wasting time actually getting started. I tried to solve this by tying the habit of writing to starting the Pomodoro timer rather than the act of writing itself. This hones in on the specific if-then protocol – and often that’s just a matter of starting as quickly as possible. And the science suggests that this “jumping in” method helps bypass procrastination (check out this article on the neuroscience of the 5 Second Rule).

I also attempted an implementation intention for starting work every day (both of the day and the night before) – but that required first forming a planning habit where I broke tasks down into small parts. I tried starting with a a throwaway set – an easy task to ease into writing. I also tried a task priming exercise - usually reading an author pep talk from NaNoWriMo. A lot of tiny actions - like the task priming Smiley Face Game I wrote about before - seemed to somehow smooth the transition between a break and getting back to work.

The key to all this wasn’t just what I did to get started, but what I did in between sets of work. So I started experimenting with small and large breaks.

I began meditating between writing sprints in order to introduce an emotional pattern break to prevent quickly getting worn out (mood changes have been shown to restore self-regulation). In my article on mIcrodosing on meditation, I discuss some of the one minute meditations I do - but I’ve also included other emotional changes, like looking at pics of cute kittens or green landscapes, both shown to boost productivity.

The Pomodoro Technique also includes larger breaks - but what do you do during them? Previously I’d just wander off and be pretty lax about coming back.

Forest bathing and walking have both been shown to recharge the mind, but are a bit time consuming. While I do try to incorporate walks, I want to try rebounding - bouncing on a mini trampoline. As weird as it sounds (and the iffiness of the studies - some believe it “recharges” all the cells in the body), I think it might introduce an energizing emotional change. Any sort of acceleration has a thrilling, charging effect on me – think rollercoasters and go karting.

But the biggest change to my schedule was taking breaks BEFORE I felt tired. I started mandating a break after 40 minutes instead of just going with the flow or going until I felt tired. Seems obvious, but it significantly extended my number of Deep Work sets.

A part from individual sessions, I discovered that what I did across time also had an effect on work.

I recently wrote about tasks that are actually optimized during periods of low willpower. One study found that people are more creative when they’re tired. So any tasks that require decision making or discernment (like editing) are best placed at the beginning of my work day. Creative endeavors like brainstorming ideas, automatic tasks, or writing that benefit from less willpower (like first drafts) are placed later in the day. A well developed planning habit that maps this all out significantly helps, or you end up getting pretty bogged down.

As the day progresses and I get more willpower-depleted, the strategies I use to perk back up change as well. Not only are some tasks optimized for low willpower, but exercises that involve exemplar priming seem to work better when you’re depleted to fuel focus.

Progression through the day in regards to energy levels was also important.

In an excellent article, the Harvard Business Review describes how managing energy is even more important than managing time. The biggest energy slump happens after lunch. One counter is altering the meal itself. I tried just having a light meal. In addition, I tried making a concoction with a tablespoon of apple cider vinegar, which a few (admittedly small) studies show improves insulin sensitivity. I also use matcha in it, which offers a smooth background caffeine buzz that avoids the crashes of coffee. In fact, in one article, the author found that simply doing a quick 30 seconds of exercise as a break offered an even better energy boost than coffee.

Getting adequate light, beauty and even the color of your work space also seem to boost productivity in a general way like getting a good night of sleep.

—

There’s a default tendency to view all of this as a matter character. In reality, there are a slew of contributing variables. Testing and retesting combinations automatically resulted in different outcomes. And it was often what I changed well before a bout of laziness that led to more optimal and sustained productivity. The system parameters herded and supported a better work day – no digging deep required.

At the end of all of this my average deep work sessions almost tripled.

And I haven’t even started bouncing yet…

—

Cultivate your work space. Make it beautiful and filled with light. Paint it a high saturated color - ideally blue for productivity (or just use a computer background).

Get a good night’s sleep. For me, that means getting to bed earlier, not drinking too much, avoiding caffeine at night, eating well, and rigorously paying attention to light. I have blue light blockers on my computer (F.lux) and phone, and try to get light at the beginning of the day (there’s a study that shows it helps with sleep - in my sleep test, it significantly correlated with helping me drift off faster).

Wake up and plan out the work day. I try to do this in sunlight with a cup of coffee (black to avoid a sugar crash). I like using the bullet journaling method because it’s easy and simple. I break down tasks into categories - ones that are urgent, ones that require more self control (like editing) and ones that require less (creative or automatic tasks).

Immediately start my Pomodoro timer. I use Tomighty, and set 4, 10 minute intervals with 1 minute breaks. I make sure to have the ticking going in the background because it’s an added reminder of the passage of time.

Set up a Deep Work session. I set my phone to airplane mode, use an app (SelfControl) to block Facebook and Reddit, and start a Spotify playlist that helps block out distractions yet isn’t too distracting in itself - I usually use the one aptly called “Deep Focus”.

Lubricate starting work. Do a quick throwaway work set (like a morning page) or read an exemplar prime (like a NaNoWriMo pep talk).

Take small breaks. For my short, one minute breaks, I cycle through a series of micro meditations during my one minute breaks - mindfulness, compassion, tantric visualizations - types that will shift my emotions in some way. Sometimes I also look at cute animal pics or videos (www.reddit.com/r/aww), affirmations, list of accomplishments I’m proud of, or gratitude statements. I sometimes watch short motivational videos or look at pictures of forests.

Take longer breaks. After 4 sets I’ll take a longer break. I try to get out into the sun and incorporate some minimum amount of movement. If you have time, walk around the block. If you can, walk in a forested area.

Harness movement and momentum. There’s a weird focus boosting effect I get when switching locations. Sometimes I’ll work at my gym before or after working out. Sometimes I’ll go to a coffee shop or a library.

Mind the afternoon slump. Pay attention to your blood sugar. Eat a light lunch or one that affects your blood sugar the least. Drink a concoction of matcha and apple cider vinegar. Stop drinking coffee in the afternoon. Incorporate short, 30 second workout sessions.

Shift into low willpower strategies. In the afternoon (or when you feel more depleted, whichever comes first) start easing back into work after longer breaks by playing the ego associative smiley face games (here’s a similar phone app called Upbeat Mind), or reading an exemplar prime, or pretend you’re Batman. Shift into automatic and creative tasks. And boost creativity by switching your screen background to highly saturated yellow.

Turn off. When you’re done, be completely done. Cal Newport advocates a shut down ritual which includes reviewing completed tasks, reviewing his future plans, and uttering a phrase to set his mind to the off mode.

Some things I have not tested (but are on my list): Essential oils/aromatherapy, the effect of different types of music or binaural beats, cold showers, rebounding, and nootropics.

But a really efficient machine is one that actually harnesses wasted energy, using both sides of the piston to turn rotors and crankshafts. I think these studies point towards such an efficient engine, one I hope can drive massive personal change.

Read More

Lydia and I have a bit of downtime between stops, so glance at a Google map to see what’s around. The map has around 50 markers pinned all over the city, from stores and restaurants to scenic views and festivals. I prepped it over a week ago in advance of our road trip to Austin, Texas.

It’s a first for me.

Despite traveling the globe for a decade I’ve always been a fly by the seat of my pants kind’ve guy. That usually translates to someone else handling the itinerary, My planning habit has changed that.

Hovering at 75 on the SRHI, my planning routine is just shy of “super habit” status. While sipping a cup of coffee in the morning I pull out my Bullet Journal and update it. The Bullet Journal Method feels perfectly suited to harness my naturally chaotic M.O. With it I can make random pages of thoughts or jot down project notes irrespective of page location, but still index it without skipping a beat.

It also allows me to organize time much more efficiently. Some wise management luminary once described life as a jar. Fill the jar with sand - the trivial stuff - and you won’t be able to fill it with rocks, symbolic of what’s really important. A better method is to fill it with rocks, then pebbles, then sand.

My central “planning dilemma” is the need to do it all. The jar metaphor isn’t just about space, it’s also about time. Planning has shown me just how powerful carving out small portions of a week can be.

Take my next book proposal - a lot of successful writers have advised that you should always be working on something else. When planning, I’ve tried to designate about 40 minutes per week to wrangling together what in my mind seems like a horrendously large project. For comparison, my first two proposals took 9 months each.

Yet in 5 sessions I’ve done a rough draft of the majority of the proposal. This includes an overview, a marketing and competitive analysis, a table of contents, all of my chapter summaries, and an outline of my first sample chapter. A simple, consistent plan has powerful compounding effects. And it appears as though I’m doing two things at once.

While planning gets me closer to doing everything, in travel it’s seeing everything that’s my main concern. I’m terrible at planning trips, but if I apply the “jot outline” approach, things go well.

I randomly list out everything I want to do with fixed events acting as anchor points. I structure the rest (the pebbles or sand) around those important rocks, and tasks - like buying tickets or getting a reservation - are assigned based on that model. With both writing and travel planning, this method grows structure from the chaos.

Lydia usually does the planning by default because she knows I’m not going to do it. A solid planning habit allows me to pick up my share of the emotional load in this, and in other smaller, pesky things. Paperwork, getting back to people, researching a festival, figuring out what parking is like - these all function like sand in that jar metaphor.

My mind tends to tense over details, which is why I often opt out of making decisions. But surprisingly, planning is also of great help in relaxing.

I’ve hinted a bit about my concept of Structured Relaxation - when left to my own devices I’ll end up wasting weekends or any time off and end up feeling less rested than before. I try to plan out “weekend menus” to give me options, and planning gives me a place to do it consistently. While I might not check everything off those menus, I do find I’m surprisingly rejuvenated and content at the end of the weekend. It’s a far different feeling than discovering I’ve done nothing but mindlessly scroll on Reddit or Facebook.

In my last article on planning I talked about long term strategy through mediocrity. A post I recently saw on Brandon Sanderson suggested that he has writing plans for 5 years in the future (and honestly, it’s probably more than that)! That’s something to aspire to, but I’m nowhere near mastering that type of strategy with writing. My problem lies in not knowing how long any give task will take, which is a rather huge issue (though it is something I’m working on). But with other projects - like knowing how long a habit will take or what vice I intend on quitting next - I’m showing marked improvement on the strategy front.

I still have a lot to learn. The temporal subcategory of the planning dilemma is one of hierarchy across time. You need to work on long-term projects, but the urgency of goals around the corner prevents you. And multitasking can be detrimental when it comes to energy, concentration, and momentum.

I think the key is harnessing the right amount of consistency over time. I have a task that I need to finish in a month from now, but I’m only working on it for about 10 minutes per week. Meanwhile, I’m working on my next proposal 40 minutes per week, a task I don’t need accomplished until a lot further off. Clearly, I need to switch this up, assigning 10 to the proposal and 40 for the task due in a month. Carefully labeling and assigning times in terms of time accrual might just be the best way to fit multiple projects into one small jar.

Meanwhile, I’m also researching advanced techniques for project management. This blogger, for example, has a particularly excellent system which uses a Bullet Journal to define, assign a time estimate, and schedule tasks. That then interfaces neatly with a Kanban board to track progress.

—

While driving back from Austin, Lydia remarks on what a great trip she had. We didn’t hit everything on the list, but we met friends and did outdoorsy stuff, tried new restaurants and visited old haunts. We did a lot, and the trip was even better for me because I (for once!) had an active hand in it.

I’m not surprised that I enjoyed my visit, but I am at how much I enjoyed planning it.

Photo credits: jars by callmekato, beach by Cristian Viarisio

I’ve written about the importance of planning before, but after attending the Dallas-Fort Worth Writer’s Convention this weekend creating a habit has never seemed more important.

I’ve always been bad at it. I’ll pick up a planner and use it for a week or so and then, like all of my habits, it’ll fade away. Across keynote speakers and casual one-on-one conversations throughout the conference, it seemed that success seemed to be a matter of luck. Some person just happen to read and enjoy a writer’s work at the right time and right place. And while that seems disheartening at first, the behavioral hack behind the scenes was the same: all the writers kept constantly sending work out into the world.

Luck can be gamed. And the key is to, as Brandon Sanderson said in one of his lectures, “always be working on something else.”

That makes complete sense but is utterly beyond me without having a long-term planning system that’s solidly in place.

So…

As soon as I get my coffee and sit down at my desk, I’ll spend just a few minutes going through my bullet journal and updating lists or reading and ranking what I need to do that day. I’ll do a bit more on Monday for the week, but even if I just open up the journal every day the habit will still count.

A) Positives

The ability to make this a part of my life will help me fill the world with writing arrows, hedging my bets to make success happen. It will also alleviate the feeling of living or dying on one proposal or pitch. This is immensely emotionally important to me. It will also help me significantly improve my craft. It will bring some amount of order to my generally chaotic life. It will help me plan for productivity experiments, and will prevent wasted down time.

It will also help me become a better person.

I think in relationships the concept of mental load is important - it almost always falls on females. I am a person who exacerbates this. I don’t plan for trips, I don’t get what I need done because I’m so disorganized, I don’t have my shit together. This forces the people around me to take up immense slack that I just assume they will carry. To both be free of that nagging feeling of constantly ignoring something in the background and to lessen the load the people I love shouldn’t have to carry is incredibly positive.

B) Obstacles

Not carrying my planner when I go on trips. Grossly overestimating time. Not having a pen on hand. Not feeling like I know it all now, when I think this will be a process of growing and adapting to what works best for me.

B-1) Workarounds

Luckily Lydia is a master of this, and I’ve already interviewed her for best practices. I think I’ll start with the basics and then add different aspects - like the 3 Ships concept or whatnot. A surprising amount of these best practices mimic what process composition writers like Jack Hart and Shani Raja describe when they talk about bringing structure to articles.

I intend to write another post on the ins and outs of this. It’s really a very foreign concept to me, but I can see it doing a lot.

Every day people struggle to get to the gym. They look in the mirror and sigh, hoping that their sweat and tears finally etch themselves onto their body. Is that an ab line, or just a hope of one?

Imagine instead if you knew that it took 10,000 crunches to gain a 6 pack. Or if you needed to deny 230 urges to become a non-smoker?

Feels more manageable, doesn’t it?

My partner Lydia has always been an organizer. And that’s a good thing - as a Senior Editor at USA Today’s online travel site 10 Best, and the production manager for their Readers’ Choice Awards, she’s got a lot on her plate. The Readers’ Choice is a national award that’s highly sought after. Cities have written articles and put out TV ads to help turn out votes. She’s responsible for promos, newsletters, producing YouTube videos, contacting experts, sourcing photos, updating PR contacts, assigning articles, weekly strategy sessions, and writing articles herself. In her spare time, she writes for another publication, is an officer in the Society of American Travel Writers where she helps organize conferences, and volunteers as a Crisis Text Line counselor.

She does all of this, week after week, seated next to me as though it’s nothing. It is mind boggling.

For her, organizing is a necessity and one that gives her “control over the chaos.” Which makes sense on many levels. In one study on sleep hygiene, writing tomorrow’s to-do list actually helped off-load worry, helping subjects sleep better. Her Sunday planning session is a relaxing ritual.

When things are finite, long-range planning like this allows you to measure the void.

The so-called “hardcore” or “pragmatic” dharma movement applies similar approaches to Buddhist meditation. According to them, practitioners tend to get lost, floating around for decades without any real progress because no progress is ascribed. While they may come and do the work, forward momentum is never quite reached. It’s a feeling I’ve likened to churning in the mud. Lots of daily work is done, but the percentage towards completion isn’t ever clear. And so completion may never come.

This is the opposite ethic of true working professionals.

The high mark of mastering a craft means delivering products on a schedule. Most experience this in tasks with clear objectives, those often handed down by bosses in normal jobs. But it starts to disappear once things get vague - like in the arts, with self development, freelancing, getting in shape, or with writing.

The process writers tend to emphasize deadlines. Legendarily productive science fiction writer Brandon Sanderson does this visually with percentage bars at the top of his site. They clearly denote how far along he is with drafts, outlining, or proofing. Writing author and teacher Holly Lisle can estimate with high accuracy when she’ll complete a novel. She writes everything, as writing coach Donald Murray would describe, “to deadline” by measuring, with buffers, how long projects will take.

George R. R. Martin, on the other hand, has famously had problems with this over the years.

In an interview with Stephen King, this difference becomes clear.

“How the fuck do you write that many books?” Martin asks. “I’ve had a really good 6 months [and] I’ve written 3 chapters and you’ve written 3 books in that time!”

King responds that he tries – despite entropy and real life intruding – to get 6 pages done a day, no matter what. And he sticks with it.

While George and I aren’t on par as writers – I find him to be an amazing one – I do get how he feels. Unlike Lydia, I’m not a natural planner, nor was I forced to be one. This seeps into almost every aspect of my life - from writing to travel planning. And while this suggests a certain freedom, it really means that I feel I’m running around with my head cut off most of the time. There’s a panic that no matter what I do in a day, it will never be enough. I just have to blindly (and rather hopelessly) march on and on.

What Lydia advises is to write down all tasks and break them into components. Estimate a time for each task, then estimate a timetable for them using a basic understanding of how you work in a day. Include flex time. Include additional tasks if you exceed expected deadlines. And adjust timings as you get a better grasp of how long they will take across projects.

She helped me to do this with the massive task now in front of me - a book proposal. The first proposal I completed was excruciating, taking 9 months to complete. I didn’t know what to do at all.

This is my third or fourth proposal. I know exactly what needs doing, and thanks to process writing, I know how to do it. And yet, it still feels equally uncertain. I can’t answer basic questions regarding a timetable. And it feels like it will last forever. And when I switch tasks, I feel totally lost.

I broke up everything with her help, overestimating the amount of time for each task, using my 20 minute Pomodoro sessions and deep focus protocol. Of course the calculations will be off the first time, but when we inputted a buffer, took out weekends and my upcoming birthday this massive, behemoth task ended up taking…16 days.

I’m still stunned.

Why haven’t I done this before?

Backing up a moment into theory, I initially thought that creating “Finiteness” – therefore predictability in long-term goals – might be another Element of Change. It allows our minds to grasp and lock on to discrete things. In that it’s similar to metrics. This “chunking” bakes in the pressure to actually complete the task in the requisite amount of time - and try to beat it. It’s an odd sense of gamification and self-competitiveness that all good metrics encourage.

If I were to think of it as another combination of elements it would be:

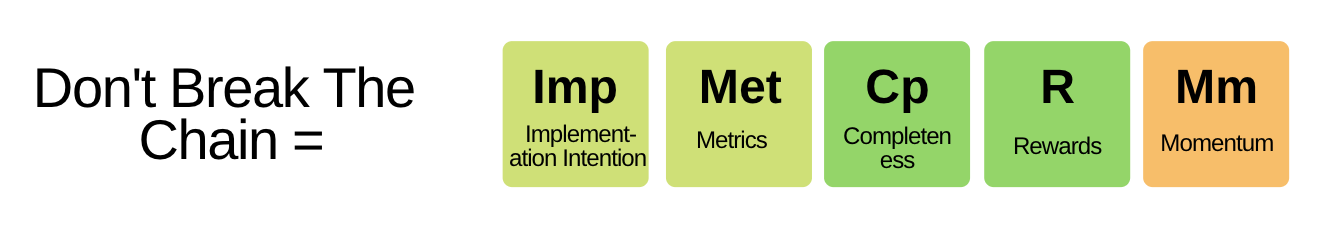

Intentional Imperfection, or “shittyness” is the element I ended up adding to the Elements of Change. Anne Lamott includes a chapter in Bird by Bird (her book on writing) on “Shitty First Drafts”. I am a huge fan of this concept. Like Tiny Behaviors, which drop quantity, Intentional Imperfection harnesses lowered quality to gain consistency. By creating a System of preplanned (Bypassing Decisions) Tiny Behaviors that you can define Metrically, you gain Momentum. Writing down what you need to do (Implementation Intention) and planning on less than optimal times for task completion (Intentional Imperfection) you suddenly have the ability to plan in advance. Adding a system of check marks or progress bars can act as a Reward.

Just the idea of such a timetable seems eminently relaxing. It makes me want to trust the process more when there are not only waypoints and progress reports but an end clearly in sight. The giddiness of seeing that number – 16 days – is unparalleled. And it doesn’t derive simply from making molehill out of a mountain. It frees me up to plan 3 or 4 steps down the line instead of hoping and praying that the task in front of me actually gets done. This also builds in the pressure to conform (Conformity is another element I’ve thought about adding), so that I can actually do the next step. I’ve always wondered how freelance writers could pitch an article about an event months in advance, and also take into account a 3 month lead time for publication after submitting the article.

I guess that’s called “strategy”.

As with all elements or new techniques, I like to see how they can be applied to other processes. With eating well, like with writing and meditation, it would be great to actually create a map of mastering eating based on the research I’ve done on quitting other habits. Financial planning in long-term steady investment strategies like the Bogelhead philosophy, gifts predictive power - rather than hoping you’ll be rich or poor if your investments fluctuate, you know how much money you’ll probably have in X number of years. For body building it’s macrocycles - being able to shift from bulking to cutting and knowing when to do it.

I have never used planners. And anytime I’ve attempted it I’ve abandoned them in short order, just like with habits as a kid. It’s almost like I grow bored or forgetful of them. Lydia believes this has to do with confronting fear. She says with planning you have to write all the things you have to do up front, and that idea is something that engages all my well honed avoidance measures. But she thinks it will ironically result in the greatest LOSS of fear in my life. When I wondered out loud how I could could counter that avoidance she gave me a measured look as if to say …isn’t your whole project about habits? Have you ever made a habit of this?

The obstacle is the way and the only way is through.

I have already fallen far behind the mark of 16 days. I think the biggest reason why is that I wasn’t planning for the less than optimal. And I think this is the key to the entire process, and why I’ve always abandoned planners. In the past, I used planning as a visual intention of optimism. I COULD get everything done by next Thursday. If I put maximal effort in, I COULD finish my project TOMORROW. When I inevitably failed at the task, the next ones I had lined up collapsed, as did my adherence to the planners.

As with Tiny Habits and lowered minimums, planning for under average performance nets greater gains through predictive power and consistency.

At some point I will have to sort out a planner. Lydia tried the Savor the Success Planner from Angela Jia Kim. She didn’t like it as much because it had too many bells and whistles and was too zoomed in on each day. But I like how Kim includes the 3 Ships concept from Chellie Campbell’s The Wealthy Spirit. This is particularly helpful for entrepreneur’s (whom the organizer is geared towards) and could be adapted easily to people who are pitching, like me. Lydia settled on the Ink + Volt planner, which she has been using for at least 4 years. She likes that it is relatively minimalist and has a built in revisiting of yearly and monthly goals.

Whatever the planner, the important thing for me is to formalize a planning habit. As I mentioned before, for Lydia this involves a Sunday morning ritual with coffee, writing a to-do list for the week, first of repetitive tasks, and then adding others, including anomalous events.

As a skeptic and cynic, depressed and anxious, the horizon has always held a vague sense of potential menace, just waiting to be unleashed. But Lydia’s planning, with all of its progress bars and completion times, is a tool to chop and dice the infinite. And for once I feel oddly relieved.

photocred: planner by Duc Ly, chess by Tristan Martin

A Better Way to Write

The Process Theory of Composition

The Writer sits at his computer, struggling to channel the Muse onto the depressingly empty page. It worked before, but today, everything typed ends up deleted. It was all so perfect the other day!

A common belief of writing is that it is an unchanging extension of the soul. Either we can write or we can’t.

In the opening lines of A Writer’s Coach, journalism professor and editor Jack Hart says:

“Novices sometimes imagine writing as a dark magic, something known only to some mystical inner circle. They pick up a professional’s finished work, marvel at its seamless perfection, and think, I could never do that.”

Later in the introduction he adds:

“The invidious mystique of writing taints the curriculum in almost every school. In literature classes, you read a great works and marvel at the genius of the writers who produced them. In composition, you struggle to knock a few clumsy sentences together. Nobody expects you to see any connection between the diva’s aria and your Neanderthal grunts.”

A better method is one that takes focus away from divinity. In the words of James Clear, an author and writer on habits, it is better to create long-term systems rather than short-term goals:

“Achieving a goal only changes your life for the moment…We think we need to change our results, but the results are not the problem. What we really need to change are the systems that cause those results. When you solve problems at the results level, you only solve them temporarily. In order to improve for good, you need to solve problems at the systems level. Fix the inputs and the outputs will fix themselves.”

I thought I was a good writer. My natural abilities got me far. As a columnist for National Geographic Traveller, my writing appeared in publications like Esquire, GQ, Vogue, and Conde Nast Traveller. But at several stages of writing I’d often be beset by writer’s block. I’d procrastinate, I’d obsess with one article, but more importantly, I was always uncertain.

In the newsrooms of the Oregonian, Jack Hart discovered that many veteran journalists had this problem. He, along with with a cabal of writers, coaches, and professors like Janet Emig, Peter Elbow, Chip Scanlan, and Donald Murray, emerged at the forefront of what became the Process Theory of Composition. Process composition championed the idea that writing, even at a high level, could be treated like any other craft.

The key is reducing tasks to component parts. Author Timothy Ferriss emphasizes this in his book The 4-Hour Chef, detailing a methodology to reverse engineer any skill.

He describes the first step, Deconstruction, as asking “what are the minimal, learnable units, the LEGO blocks, I should be starting with?” This prevents anxiety by eroding the scale and impossibility of complex behaviors. When applied to writing, it becomes clear that many issues originate from executing multiple processes at once.

As a nonfiction writer, my process involves layers of Creativity, Structure, Transitions, Ledes and Kickers, Research, and Polishing.

Over the course of this article, I’ll tackle each stage and offer general tips and tools. In the Appendix I’ll also provide a meta document with all of the layers I used to create this very article, which should provide a bird’s eye view of the process.

The blank page is always the first challenge for any creative. Perhaps the best methods to generate ideas surprisingly come from the world of advertising. On Madison Avenue, artists and writers were, perhaps for the first time, forced to adhere to corporate deadlines where millions were on the line. One powerful idea generator unlocked creativity by lowering standards, setting time limits, and increasing output. The key, however, is to treat it mechanically:

Creativity is a physical process, not a mental one. It's also something that can be easily taught through certain exercises. While some people are naturally more creative than others, those that aren't can make up for their lack of creativity through simple processes.

This activity, described to a Redditor by Rory Sutherland (an executive of Ogilvy Advertising) is called "scamping":

“The trick is to think as little as possible, and work as fast as possible. You'll probably start out with some dumb ideas. That's fine. The goal is to bounce from one dumb idea, to a less dumb idea, and so on. You'll soon find nuggets within these dumb ideas, and start building upon them. Personally, I wouldn't stop until I'd gone through an entire stack, which would take about two hours.

Once you're finished, it's simply a process of elimination. Go back through all your ideas and start sorting them into two piles: good and bad. Once you've done that, take the good pile and sort them again by good and better. Keep doing this until you've narrowed it down to five ideas.”

Game designer Nick Bentley describes a version of this as the 100:10:1 Method. Either method bypasses the muse – or at least summons her when and where you want. And though the idea of the tortured artist desperately searching for ideas appears ubiquitous today, it wasn’t always so.

In fact, in “Blocked", The New Yorker describes how it originated in a certain place and time.

“Writer’s block is a modern notion. Writers have probably suffered over their work ever since they first started signing it, but it was not until the early nineteenth century that creative inhibition became an actual issue in literature, something people took into account when they talked about the art. That was partly because, around this time, the conception of the art changed. Before, writers regarded what they did as a rational, purposeful activity, which they controlled. By contrast, the early Romantics came to see poetry as something externally, and magically, conferred.”

Another technique for circumventing blocks is to disassociate yourself from them. You can do this by framing the work as an explanation to a friend (that’s how this article got its start for me), or perhaps an argument with an enemy. Legendary journalist John McPhee’s advice is to write a letter to mom:

“You are writing, say, about a grizzly bear. No words are forthcoming…You are blocked, frustrated, in despair… What do you do? You write, ‘Dear Mother.’ And then you tell your mother about the block, the frustration, the ineptitude, the despair. You insist that you are not cut out to do this kind of work. You whine. You whimper. You outline your problem, and you mention that the bear has a fifty-five-inch waist and a neck more than thirty inches around but could run nose-to-nose with Secretariat. You say the bear prefers to lie down and rest… And you go on like that as long as you can. And then you go back and delete the ‘Dear Mother’ and all the whimpering and whining, and just keep the bear.”

If the ideas are the blood and guts of a story, then structure is its bones, the organizational principles that make it stand.

Most of us were taught outlining as children, but a better method that interfaces with scamping comes from Shani Raja, a former editor at the Wall Street Journal, Economist, and Bloomberg. In his Udemy course “Editing Mastery: How to Edit Writing to Perfection” he describes specific steps to construct a logical scaffolding for any article.

The steps are simple:

Atomize the ideas and list them out, one per line.

Tag each one with a general family marker.

List out all the families.

Rearrange the families in an order that works best.

Physically move the points to the families.

Physically rearrange the points within each family.

Jack Hart further talks about this in A Writer’s Coach where he dubs the process a “jot outline”:

You go through your notes and list the main topics you want to cover, jotting them down or typing them on the computer screen as you find them. If you’re using a computer, you then block-move those broad topics into logical order.

The act of writing down your few main topics, in order, gives you a step-by-step approach to the chaos of details you often face when information gathering ends. It relieves panic because it allows you to ease into the writing incrementally. It creates some distance between you and the story. And it’s a relaxing ritual.

If you’re facing a deadline, you may think you don’t have the time to outline. But you probably don’t have time not to. -A Writer’s Coach, p. 35

When BBC documentarian David Attenborough transports you from Amazonian rainforests to the icy Himalayas the way he did it is what you forget. It seems effortless, like a wizard whisking you to another, far distant land.

Shani Raja describes them as “narrative turns.” They offer a smooth intro to each new section, forming a secondary infrastructure within the article.

And as a viewer you accept it, almost unconsciously.

Great writers, documentarians, and especially stand up comedians use them to elegantly shift from one, seemingly unrelated topic to another. In this blog post CEO and Kibin Co-Founder Travis Biziorek describes how transitions make or break standup routines.

Transitions are so important that Conan writer Laurie Kilmarten shared a compilation of them used as a go to reference for fellow professional writers on the show.

Categorization is key to breaking down processes, and in composition it allows writers to hone in and practice elements of the craft. By analyzing a number of articles, and how writers move from one topic to the next, we can classify transitions into categories. Luckily, there doesn’t seem to be that many of them. Over the years I’ve only been able to identity about 20, which I’ve listed in the Appendix.

Beginnings and endings are another stumbling block, even for highly advanced professionals. John McPhee even wrote an article in the New Yorker discussing his difficulty finding good endings.

But many of the process “wise guys” have solved this in the same manner that I solved transitions. Jack Hart had his “Lexicon of Leads” (Hart, p. 49), and Chip Scanlan describes his “Encyclopedia of Endings” in an article for the Poynter Institute.

The key is to simply analyze, categorize, and keep the lists as cheat sheets. I’ve included my expanded versions of both in the Appendix.

And when confronted by an actual article, follow Don Murray’s advice:

“Draft a dozen leads, or two dozen. Just the first line or so. Do it quickly – a matter of one minutes for each one – until you find the lead that focuses the story. Then develop that lead.” - Writing to Deadline, p. 135

In the past, first drafts were the initial high wall to hurdle over and I often couldn’t make it. With the mechanics of the article sorted, the bar to jump is a lot closer to the ground. All the mechanics are at play, smoothly guiding you from introduction, families of points, transitions, all the way to endings.

However, research can easily become endless, especially when you’re writing nonfiction. That is why it’s best to do it at this phase. This stands in contrast with the usual method, with potentially endless research at the beginning. While I think research is often a necessary precursor if you don’t know what you’re saying or have absolutely no knowledge in the first place, the problem is that it can end up becoming a time drain. Perfectionism and completism, two traits all-too-common in writers, function to make this a dangerous stage where many never emerge.

If you’ve done some initial digging and know what you have to say, then follow the preceding stages first. Holes can clearly be marked with the tag “TKTK” - the traditional journalistic method for indicating that further information will be added later

Afterwards, fill in the gaps. With this, research is hemmed in and highly targeted. It’s more like a puzzle piece with clearly delineated borders than an infinitely deep, time-sucking maw.

While you might have the full article complete, it’s much like, as Stephen King describes in On Writing, a fossil that you’ve found, still buried in the earth.:

“Stories are relics…the writer’s job is to use the tools in his or her toolbox to get as much of each one out of the ground as intact as possible…To get even more of it, the shovel must give way to more delicate tools: air hose, palm-pick, perhaps even a toothbrush.” - On Writing, p. 163 - 164

I find polishing to be a matter of repetition. As with scamping, the key is writing and rewriting with minimal in-the-moment editing. Keeping a synonym finder open, continue changing small elements without really stopping, using intuition and gut reactions to know if a word or fragment is correct.

Done correctly it’s very similar to the adage of monkeys on typewriters producing Shakespeare.

The only difference is you’re using discernment to know when you’ve managed to hit on the well turned phrase.

Visually, this takes the form of a miniature bit of evolution, with the constant writing, synonym finder, and repetition acting as a genetic drift across successive generations. Meanwhile, your instinct in keeping fragments acts as natural selection protocol. The key is, like scamping, to make the process mechanical and continuous. This is a knack to be developed through practice, and I’ve mentioned methods to develop it in the Tools section.

But for Shani Raja, polishing is all about adding another layer, especially with implanting thematic elements and evocative verbs. He uses this stage to goes on a hunt for common mistakes, like redundant phrasing and passive voice. With Jack Hart, this layer can also mean adding similes, detail, and color.

While the nitty gritty is very important, here are some general suggestions for the overall process.

One great tip is what Hart calls his First Law of Writing Improvement:

“A problem visible at any one stage of the writing process usually results from something that happened at the immediately preceding stage.” - A Writer’s Coach p. 7

I have noticed this to be very true. In his MasterClass, James Patterson advises moving quickly from one draft to the next to prevent inertia from gunking up the system. While Stephen King doesn’t usually do as many drafts as Patterson, he does advocate finding the outlines of a story as fast as possible.

Don Murray harnesses this for problems with writing beginnings and endings. And while it may sound tedious to write so many, it tends to save time in the long run:

“Drafting leads or last lines can be a good technique for meeting a deadline. The time invested to draft just a half a dozen leads pays good returns if you find the right lead instead of stumbling through a piece following the false direction of a bad lead”. -Writing to Deadline, p. 11

All of these techniques put continuous focus on the mechanics of the entire process rather than individual stages.

Another useful technique is to see each stage as recruiting different personalities.

According to Jack Hart:

“Somehow they’ve [productive writers] learned what appears to be the secret to successful drafting – operating with a split personality. They have one mind-set when they’re getting through a first draft. But they adopt a completely different approach when they go back to polish the copy into finished form.

The happiest, most productive writers approach their rough drafts as a literary version of Mr. Hyde. They cast civilized restraint aside, letting an uninhibited process of creation carry them quickly through the first version of the story. They don’t stop. They don’t revise. They don’t look back…

Only when they’ve finished with the draft do they slip back into a Dr. Jekyll persona. Then they sweat each detail, checking facts for accuracy, revising sentences for rhythm, and scrutinizing words for precise meanings.” - A Writer’s Coach p. 38

I tend to to use a few more personalities.

For scamping, imagine a part of yourself that’s a confident yet Whimsical Creative. I know several of these personality types, the ones that are free spirits, who often don’t have a lot of new or unique things to offer, yet boldly proclaim them as though they’re god’s gift to literature – spelling mistakes and all. Fundamentally, they believe that they are special and should be heard. Or alternatively, it’s the monkey on a typewriter, never stopping, gleefully pounding away to the music of the keyboard. This is perfect for scamping, rough drafts and some level of polishing, where cynicism is just not useful.

The Analytic is perfect for mechanical aspects of the process. He’s the guy who doesn’t like the confusion of soft skills, but loves puzzles and is utterly enthralled with simple tasks with discrete rules. Or, the Architect, focussing on the big picture, like Tony Stark amusedly designing the first Iron Man suit. Playing with concepts, he throws this away, keeps that, changes it up to look at different configurations on a whim with none of the urgency for a final product. The entire article is like a jigsaw puzzle, carved so every piece is unique and fits just so. This is perfect for the organizational phase, where word choice is inconsequential.

The Magician is trying to pull a beautiful fast one on the audience. His hand movements may be highly technical, his tricks may involve complicated bits of string or false thumbs that look oh so mundane in the light of day. But to the audience he’s effortlessly whisking them from one place to the next. These are transitions - there are only a few, they are very mechanical, but when done right you don’t even know they’re there.

The Archivist loves diving into facts and figures. She’s also a bloodhound and a detective, sleuthing for details. Bookish, she has to be held on a tight leash, but when reigned in she targets searches and comes back out again with summaries to be placed neatly into the holes carved out for her by The Analytic.

And lastly The Queen is the editor, she who must be appeased above all else. She’s arrogant, anal retentive, the ultimate fashionista with unquestionable taste, demanding the highest of standards. And if she doesn’t like what she sees, she banishes the section to another one of her earlier underlings. She’s the one in charge of the details and formatting.

The other steps are combinations of these personalities. The Monkey-Creative pounds on the keyboard to get through the first draft and for polishing a turn of phrase, though it works with the Editor/Queen to know what to keep. The Analytic works with the Magician for transitions, because really there are only a few and it’s a largely an act of matching the two together. The same occurs with beginnings and endings - there are only a few categorically, but the Magician makes it hit home with the panache of an entertainer, and the editor presides over it, making sure it all hangs together. The researcher is like a hermit searching for truth, but has to be hemmed in to prevent him from wandering off forever.

Luckily we don’t have to just rely on smoke and mirrors to recruit different skills.

Scamping can be practiced. National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) is a program that focuses on word output rather than content, with a supportive community and a gamifiied system in place to fuel mastering the art of pounding on the keyboard. While that was the system that really helped me master it, Write or Die is another method. It offers a mode where the program starts deleting words if typing stops for a few seconds, forcing users to write with, as the Guardian put it, “a virtual gun to the head.”

Writing coach Don Fry suggested writing with the screen blank if you’re encountering resistance completing a first draft. Complete a jot outline, print it out, position it on your computer monitor, and begin typing. This forces you to ignore typos or grammatical errors. Since you don’t know where you are you have to go all the way to the end (from A Writer’s Coach, p. 40).

Online synonym finders are incredibly useful for discovering that word that’s the perfect choice but just outside your mind right now. Some offer visual similarity and meaning maps, with options to select for length or starting letters.

Brainy Quote is a great tool for beginnings and endings. While the quote-beginning or quote-ending is somewhat passé, it is definitely a great welcome addition, and can spur on thought on other avenues to begin and end pieces.

Having a list of Transitions, Ledes, and Endings on hand is key for those sections. I’ve included these lists in the Appendix.

Scrivener is a fantastic program for layering drafts, and easily moving back and forth between them. You can view split screens of different drafts, which is handy when, say, writing a first draft while looking at a skeletal outline. It also has a cork board feature where you can move categories around visually.

When looking at the big picture you have to learn to “kill your darlings” - get rid of smaller aspects that you might really like in order to further the work as a whole. Shani Raja says that he used to either print the article out, or change the font and size to act as though the piece you toiled over is someone else’s, subject to brutal objectivity.

One of the best pieces of writing advice comes from fantasy author Brandon Sanderson, whose excellent writing classes are recorded on Youtube: Always be working on something. It’s echoed by many other prolific writers. It helps in terms of pitching and in disassociating to maintain objectivity in edits. Sometimes you get too close to your work, and taking time off, ideally by working on something else, is key. For that I use Trello.

Often touted as software for collaboration, I find it useful to visually keep track of multiple projects. With it I can enter into any writing stage and know exactly where I am and what I need to do. If I get tired of one stage of the writing process, I can go and work on another stage with a different article.

This manner of writing is dramatically different than the traditional method.

For one, there’s a reliance on external tools. When you’re constantly referencing lists of ledes, or robotically reordering thoughts to produce structure, you emphasize how mindless the entire process can be. And that has clear benefits. Overthinking is perhaps the leading cause of writer’s block. And idea generation appears to be fueled by NOT being so attentive. The ability to push forward on writing despite being tired or distracted results in constant forward momentum.

The line between mindless and mindful also offers a great diagnostic tool. When discussing Olympic lifting in his book Becoming a Supple Leopard, physical therapist Kelly Starrett explains that stressors reveal faults in the process. Add more weight or faster repetitions and a coach can clearly see the weaknesses in the mechanics of the lift. When adding stressors – writing while tired, with distractions like a TV on, or writing for time – the process writer can spot weaknesses in the procedure. The cure is often more training or breaking down the process into greater detail.

The process method offloads weight from needing to think really hard about any one thing. This results in greater output and the ability to write virtually anywhere. More output allows for more opportunities to practice, rather than being cramped and stymied by needing a commission or a perfect place to concentrate. It also prevents the biggest problem in writing - psychology. Writer’s are often crazy alcoholics, drug addicts, or depressed - even the successful ones end up committing suicide. There’s a reason for this. There are no metrics for good writing. Almost any other type of learning has something our minds can latch onto to improve. And if we can’t clearly improve – or assume writing is a function of who we are – happy writers become the exception.

Over the last few months I’ve experimented heavily with this method, and it feels weird.